by Hugh Wyatt

When my wife called a college classmate, Virginia Dabney, recently to chat, I asked her to make sure, when she was done talking, to put Virginia's husband, Bill, on the phone. I'd first met Bill a few years ago when Bill and Virginia hosted my wife and me at their beautiful spread, "Michie's Tavern," in the foothills outside Lexington, Virginia, and I had a few things I had to ask him.

I may have mentioned Bill in the past. Like me, Bill started out at Yale, but unlike me, he didn't go the whole Ivy League route. He was a few classes ahead of me, but he bailed out of the Ivy League after freshman year, and enlisted in the Marine Corps. As a private.

After three years, during which he'd made it to the rank of sergeant, his enlistment was coming to an end, and he started thinking long-term.

He started thinking about a career in the Marines. But not as an enlisted man - as an officer.

That decision in itself ought to tell you plenty about Bill Dabney: at a time when college men feared the draft, here was a guy who'd already put his time in, as a grunt, and now, with tuition money guaranteed by the GI Bill, he was free to go to the college of his choice, and prepare for the career of his choice.

His choice was a career in the Marines, and his choice of a college a military college.

"I was so impressed by the dedication and competence of the officers I'd seen," he told me, "and I thought, 'this would be a great way to spend a career.'"

He told me he did a lot of investigating, asking Marine officers what college advice they'd give a man in his position who wanted to become an officer himself.

"To a man," he told me, "they said, 'Go to VMI.'"

(VMI - Virginia Military Institute, tucked away in the Shenandoah Valley, has a rich military tradition,dating from its founding in 1839. When the "War Between the States" - the Civil War - broke out, VMI students and graduates, loyal to their home state, fought for the Confederacy. A VMI professor of physics, Thomas Jonathan Jackson, distinguished himself in battle as General Stonewall Jackson. One of the most famous moments in VMI history was the Battle of new Market, in which VMI cadets turned back Union forces and halted their advance up the Shenandoah Valley. Those young men paid the price - ten of them were killed and 47 were wounded. Months later, VMI itself would pay the price, when Union soldiers shelled and burned its buildings. Following the Civil War, VMI reopened, and since then has remained true to its misson "to produce educated, honorable men...ready as citizen-soldiers to defend their country in time of national peril." Nearly 300 VMI graduates have become generals or admirals in our armed forces; more than 300 of them have given their lives in World Wars I and II, Korea and Vietnam. The most distinguished VMI graduate was General George C Marshall, a great man of war and a great man of peace. As Chief of Staff during World War II he directed the American war effort and as Secretary of State following the war, he authored the Marshall Plan for rebuilding war-torn Europe.)

It cost Bill next to nothing to attend VMI. He explained:

"The G.I. Bill paid $990 toward tuition - $110 month for nine months. If you lived in Virginia, which I did, VMI cost $1000. So at the start of every year, I faithfully walked down to the office and handed them a $10 bill."

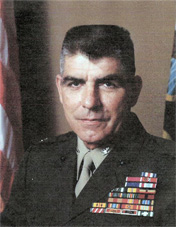

After graduation, and a commission as a Marine second lieutenant, Bill embarked on a long, impressive career, retiring as a Colonel

Last April, my wife happened to be glancing through her alumni magazine, and she said, "there's something in here about Ginger (Virginia's nickname in her college days) and Bill," and handed me the magazine.

I read the small note, and said "Holy sh--! It says here that Bill Dabney was awarded the Navy Cross!"

I had to explain to my wife that the Navy Cross - along with its Army counterpart, the Distinguished Service Cross - is second only to the Medal of Honor as an award for military valor and service.

And then, after doing a little digging, I began to find out a lot of things I'd never known about Bill Dabney.

Bill was right there, on Hill 881S, to be precise, during the 77-day Siege of Khe Sanh in Vietnam.

For 77 days, From January 21, 1968 until April 8, US Marines, including Captain Bill Dabney and his company, were surrounded and constantly bombarded by a superior force of North Vietnamese. Their only means of supply - their only contact with the outside world - was by heroic helicopter pilots, risking their own lives to fly in under heavy enemy fire.

For most of those 77 days, the situation seemed hopeless, until finally, on April 8, US forces broke through to end the siege.

That was 1968. In April, 2005 - 37 years later - after someone finally found some missing paperwork, Bill Dabney received the Navy Cross.

Bill, like all true combat veterans, deflects any attempts at congratulations or praise. True to his chosen profession, he immediately changes the discussion to the men who were lost at Khe Sanh.

I'll tell you one thing - back when I was coaching a group of young men who were headed inevitably for a winless season, I wish I'd known about the ordeal Bill and his young men went through years ago. It certainly puts any "suffering" you go through during a football season into proper perspective, and it demonstrates that in life, real winning is persisting and surviving in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds - something that can't be done without teamwork.

There is one further thing worth mentioning about Bill. Virginia's father was also a VMI graduate and also a Marine. A Marine general. A Marine icon. Perhaps the most famous of all Marines. It took a hell of a man even to ask for the hand of Virginia Puller, the daughter of General Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller", and a hell of a man to meet with his approval. Bill was that man.

Undoubtedly, Chesty Puller would have been very proud to see his son-in-law receive the Navy Cross.

---------------------

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the

NAVY CROSS to

COLONEL WILLIAM H. DABNEY

UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS

for service as set forth in the following

CITATION:

For extraordinary heroism while serving as Commanding Officer of two heavily reinforced rifle companies of the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, in connection with operations against the enemy in the Republic of Vietnam from 21 January to 14 April 1968.

During the entire period, Colonel (then Captain) Dabney's force stubbornly defended Hill 881S, a regimental outpost vital to the defense of the Khe Sanh Combat Base. Following his bold spoiling attack on 20 January 1968, shattering a much larger North Vietnamese Army (NVA) force deploying to attack Hill 881S, Colonel Dabney's force was surrounded and cut off from all outside ground supply for the entire 77 day Siege of Khe Sanh. Enemy snipers, machine guns, artillery, and 120-millimeter mortars responded to any daylight movement on his position. In spite of deep entrenchments, his total casualties during the siege were close to 100 percent. Helicopters were his only source of resupply, and each such mission brought down a cauldron of fire on his landing zones. On numerous occasions Colonel Dabney raced into the landing zone under heavy hostile fire to direct debarkation of personnel and to carry wounded Marines to evacuation helicopters. The extreme difficulty of resupply resulted in conditions of hardship and deprivation seldom experienced by American forces. Nevertheless, Colonel Dabney's indomitable spirit was truly an inspiration to his troops. He organized his defenses with masterful skill and his preplanned fires shattered every enemy probe on his positions. He also devised an early warning system whereby NVA artillery and rocket firings from the west were immediately reported by lookouts to the Khe Sanh Combat Base, giving exposed personnel a few life saving seconds to take cover, saving countless lives, and facilitating the targeting of enemy firing positions. Colonel Dabney repeatedly set an incredible example of calm courage under fire, gallantly exposing himself at the center of every action without concern for his own safety. Colonel Dabney contributed decisively to ultimate victory in the Battle of Khe Sanh, which ranks among the most heroic stands of any American force in history.

By his valiant combat leadership, exceptional bravery, and selfless devotion to duty, Colonel Dabney reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service.

For the President,

/s/ Gordon R. England

Secretary of the Navy

-------------------------------------------

-------------------------------------------

The following is unattributed, but much of it is in Bill Dabney's own words...

Capt. Bill Dabney, a fearless leader of men during the siege of Khe Sanh is described by his colleague, Capt.R. D. Camp in his book, "Lima VI" as "a big, naturally taciturn man, a Naval Academy dropout and Virginia Military Institute graduate who had served an enlisted tour in which he made sergeant. A superb leader of enormous personal stature, Bill's standing in the Marine corps was considerably enhanced by his marriage to the elder daughter of the Marine Corps' legendary beau ideal, Chesty Puller."

Colonel William H. "Bill" Dabney, USMC (Ret), 70, was presented the Navy Cross on April 15 in Lexington, Va., at Virginia Military Institute, his alma mater, Class of 1961. It would be the last and most senior medal of many other medals for valor Bill Dabney has received since enlisting as a buck private in 1954. Yet those who know Dabney say the medal is not about him. For Marine officers, it can never be about them, but rather about those whom they lead. The veterans came, 37 of them, from across the country to VMI, to once again honor a man who led them by example and stood by them for 77 harrowing days on a hill called 881 South in Vietnam.

Virginia Military Institute is nestled in the Shenandoah Valley well above the Virginia fall line. It is a long way and a long time from an off-ramp of the Ho Chi Minh Trail known as Khe Sanh, and Hills 881 North and South. VMI and Vietnam are pungent memories. The former recalls the pleasant musk of gray uniforms, white belts, polished buckles and shakos on parade while the latter is of dust-caked helmets and tattered uniforms stinking of one's own filth while hunkered down in the laterite clay between burlap sandbags.

Hill 881S: The Marines there burrowed deep on Dabney's orders, which essentially admonished them to dig, dig, dig to make the trenches deeper. Sleep by day and dig by night. He promised: "I will report the first man I see without his flak jacket and helmet!" His men later would say, "Thank God he made us do it." It had become accepted as a truism, between shovels of clay, "There are only two ways to get off this hill: flown off or blown off."

They were strong, tough men of "India" and "Mike" companies, 3/26. Surrounded by the communist North Vietnamese Army (NVA), they daily risked life and limb for each other. They were so tough they took their R&R at Khe Sanh Combat Base, and they improvised not only to survive, but also to leave an indelible memory of pain on those enemies who would be fortunate enough to survive. The Marines took an unrelenting and brutal pounding and with cool efficiency provided what help they could to other Marines also under siege at Khe Sanh four miles to the east. And in doing so, they inspired others from all U.S. forces providing support in one form or another to the beleaguered garrison at Khe Sanh.

One reason for their tenacity was their "Skipper," Captain Bill Dabney. At 33, he was a well-muscled Mustang who mastered small-unit tactics and creatively commanded an assortment of trench-filthy leathernecks standing up against hordes of NVA infantry and sappers looking to make Khe Sanh another Dien Bien Phu and Hill 881N another Battle of the Little Bighorn. The Marines, however, were neither the French nor the 7th Cavalry, and they boasted when Dabney wasn't in voice range, "Ya know, the Skipper's Chesty's son-in-law," referring to Marine Corps legend Lieutenant General Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller, USMC (Ret), winner of five Navy Crosses.

They had dug in since 26 Dec. 1967 on Hill 881S and Hill 861 (more than a mile east), regimental outposts that had been seized from the NVA in bloody battles the previous spring.

North Vietnamese Army replacement units had been spotted coming down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. They'd made a left somewhere near Lao Boa, a Laotian ghost town, and Co Roc Mountain, whose formidable cliffs were shrouded in clouds and mystery. Then the NVA units would simply disappear and it became exceptionally quiet.

That was until a Marine reconnaissance team walked into a platoon-size ambush near Hill 881N on 18 Jan. 1968. Dabney sent a platoon from India Co to recover equipment abandoned by the recon team. The platoon ran into what was estimated to be at least a company of NVA.

His interest piqued and antenna up, Dabney knew he needed to quickly head off whatever the NVA were planning. He requested to make a company-size reconnaissance-in-force to Hill 881N about a mile away.

Mike Co, less one platoon, was to hold Hill 881S while India left the knoll and fanned into the jungle below and between the two hills. India Co pushed north and ran headlong into an NVA battalion doggedly marching south. Dabney had forced the cover and shrouds of mystery to come off the NVA, and the bullets, grenades and mortar rounds flew. By nightfall regimental commander Colonel David E. Lownds radioed "India Six Actual" (Dabney's radio call sign) to break contact and get back up 881S. Dabney's men were fighting the battalion that was walking point for two NVA divisions preparing an attack on Hills 881S, 861 and Khe Sanh.

The area erupted into firefights, artillery duels and close-in aerial bombing brought on by a Marine regiment under siege.

"During the entire period, Colonel (then Captain) Dabney's force stubbornly defended Hill 881S, a regimental outpost vital to the defense of the Khe Sanh Combat Base. Following his bold spoiling attack on 20 January 1968, shattering a much larger North Vietnamese Army (NVA) force deploying to attack Hill 881S, Colonel Dabney's force was surrounded and cut off from all outside ground supply for the entire 77 day Siege of Khe Sanh."

As the senior officer, command of Hill 881S and the Marines on it fell to Dabney. Initially it made for crowded conditions with approximately 400 Marines and corpsmen. In addition to India and Mike companies, there were two 81 mm mortars, two 106 mm recoilless rifles and three 105 mm howitzers from Charlie Btry, 1st Bn, 13th Marines. At times, casualties reduced that number to about 250 Marines and corpsmen. Capt Dabney remained with his men through it all, always observing and counting ways to kill his enemies.

"Enemy snipers, machine guns, artillery, and 120-millimeter mortars responded to any daylight movement on his position. In spite of deep entrenchments, his total casualties during the siege were close to 100 percent. Helicopters were his only source of resupply, and each such mission brought down a cauldron of fire on his landing zones. On numerous occasions Colonel Dabney raced into the landing zone under heavy hostile fire to direct debarkation of personnel and to carry wounded Marines to evacuation helicopters. The extreme difficulty of resupply resulted in conditions of hardship and deprivation seldom experienced by American forces."

"Thank God for Marine air," wrote Dabney for the Web site "The Warriors of Hill 881S." Dabney's call sign was India. He recalled the following transmission with the CH-46 helicopter pilot with Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 364 "Purple Foxes" (whose call sign was "Swift")." 'Swift, India. You're taking rounds above your blades!'" 'India, Swift. Roger.' The pilot maintained his hover, holding the ramp against the hill. Five casualties aboard now, then another burst from the NVA twin .51s [caliber machine guns].

" 'Swift, India. Hits in your right engine!'

" 'India, Swift. Roger.'

"The pilot continued to hold his hover. The engine started smoking. Another burst. This one hit the deck beside the ramp, catching a stretcher-bearer in the leg. The crew chief jumped off the ramp and pushed the stretcher in, then dragged the wounded bearer aboard. One more emergency wounded to go. We got him aboard, and my HST [helicopter support team] man waved the 'bird' away. (Two of the priority medevacs [medical evacuations] had been stretcher-bearers and had remained aboard. The remaining four and one permanent routine medevac could wait for the next helicopter to arrive at the hill.)

"Just as the helicopter began to move away from the hillside, a couple of rounds from another burst of .51s went through the Plexiglas above the pilot's head. I didn't call.

"Figured he knew about that! The bird limped away, down toward Khe Sanh, black smoke trailing from the right engine.

" 'Swift, India. Thanks.'

" 'India, Swift. Welcome, Anytime.'

"He meant it too! Damnedest feat of pure guts, superb airmanship I'd ever seen! And so it went for 77 days."

As hills around Khe Sanh go, 881S stands out. Any activity, especially that involving helicopters, was noted by everyone in the area. To make matters worse, landing zones tended to be crowded.

Approximately 20 to 30 Marines were forced to work exposed to fire during helicopter operations. "Given volume and accuracy of mortars," Dabney wrote, "we often took more casualties, sometimes multiple."

According to Dabney, "As incoming got more frequent and more accurate … helos picking loads up were at greater risk, and loads themselves were often damaged by shrapnel. We figured out that the NVA tended to leave mortar tubes registered wherever they'd fired the last round, so we switched zones often."

Dabney says "Super Gaggle," a unique logistical support tactic devised by the First Marine Aircraft Wing, contributed to the survival of his Marines and the accomplishment of their mission.

"We grunts had a problem, but the zoomies came up with the solution. It was brilliant! In the first four weeks of battle, six birds were downed on Hill 881S alone, along with a bunch of WIA [wounded in action] aircrews (I don't know how many, since they reported casualties separately). We lost 100 plus KIA [killed in action] or WIA getting them in and out. In the seven weeks after Super Gaggle started, zero birds were downed (although a few were hit by antiaircraft fire), and we had perhaps 20 WIA and zero KIA during resupply. Wow!"

Super Gaggle operations, according to Dabney, required the Marines to register all their mortars on known or suspected AA sites. "At about 10 minutes prior [to helicopter resupply missions, the Marines on 881S would] fire all mortars with white phosphorus (WP) rounds on NVA AA sites. Four A-4s [Skyhawk attack jets] would then attack mortar-marked sites with Zuni rockets. Two more would then drop delay cluster bomb units (CBUs) and high-drag 250-pound bombs in valleys north and south of the hill. Then they would drop napalm along both sides of the hill about 75 to 100 meters out to discourage NVA who would lie on their backs and fire up into the bellies of birds with their AK47s." Finally, two more would lay a WP smokescreen on either side of the hill.

This gave Marines on 881S about two minutes in which helicopters could "land, deliver, pick up [and] get out. What amazed us was that it always worked, even the first time.

"My guess, based on knowledge of Hill 881S casualties both before and after Super Gaggle, is that it saved 150 to 200 casualties and perhaps half a dozen birds."

A special bond developed between the Marines on Hill 881S and the aircrews of HMM-364 and HMM-262, who were the primary source of resupply and only link with the outside world. Dabney said his Marines "knew the Purple Foxes and other helo folks also cared."

Aircrews tried on one occasion to get in several gallons of ice cream. It took awhile and Marines waited until dark because of enemy fire to retrieve the supplies from the landing zones. By then most of the ice cream had melted and the containers were punctured with shrapnel, indicating the aircrews took fire trying to deliver their gift. Although Dabney's Marines didn't get to enjoy the treat, they appreciated the thought. "More than once we watched a crewman lean out a window to toss a bundle of magazines into the zone. We loved them, especially Playboy ."

"During the 77-day siege, we never called for a 'routine' medical evacuation. For us to subject the CH-46 crews to unnecessary exposure was not an option."

When Dabney recalled the bravery of the helicopter crewmen, he also remembered the Shore Party Marines serving as HST. "I have always thought of them as my HSTs. They did, as a matter of routine, what would have, in any other circumstances, been deserving of many heroic awards. I do not recall any medevac, resupply or external load hook-up where the zone was not 'hot.'

"The antiaircraft rounds were always whipping by and the 120 mm mortar rounds were often 'on the way,' and they knew it, yet they did their duty till the bird was gone, then ran like hell and dove into the nearest hole. (I often thought that the way they stood, with their backs to the NVA guns as they guided the helos in, was a superb gesture of disdain.)"

"Nevertheless, Colonel Dabney's indomitable spirit was truly an inspiration to his troops. He organized his defenses with masterful skill and his preplanned fires shattered every enemy probe on his positions."

Dabney recalled the reality. "Our time spent on the hill always seemed a bit surreal, as if we were TAD [temporary additional duty] on another planet.

"I had no rank insignia (not a good idea to wear around NVA), hadn't bathed or shaved in three months. My flak jacket was so worn the plates were falling off, and my trousers were so rotten they'd split at the crotch. I was indecent."

Dabney needed some way for the troops to identify him from a distance, so he didn't wear the camouflage cover on his helmet. "Figured that if I needed camouflage on my helmet, we were all in deep kimchi . We were all a bit scrawny [and] couldn't have passed the PFT if our lives depended on it (PFTs didn't exist then, anyway), but we could hit the deck and roll faster than any other Marines still alive."

It was a hill that was constantly slammed with ordnance and an always-looming threat that an enemy massed in force would, with fixed bayonets, come across the wire. In the meantime the Marines kept busy "ducking rounds, running CAS [close air support], working birds in daytime, pulling in loads, improving defenses and standing 100 percent watch from midnight till dawn 'cuz that's when NVA was likely to attack. Troops did most of their sleeping in daytime. It not only kept them under cover, but saved water and thus birds, since they weren't working in the heat of the day.

"It took a full external load per day just to get us enough water to drink, cook and clean wounds. I took some heat for troops not shaving, not much. No way was I going to ask the Purple Foxes to take those risks so we could look pretty."

Some smart-thinking artilleryman at Dong Ha came up with the idea of filling 155 mm howitzer canisters with water. The canisters were strong and were not likely to burst if dropped. "If rounds hit nearby, we'd lose a few, but most would still be full when we went out after dark to clear zones (too dangerous to clear them in daytime)."

One of Dabney's corpsmen suggested using empty canisters for excrement. "Fill 'em up, screw the top down tight, and pitch them off the hill. That way we didn't have to go through the hassle of getting diesel fuel up and burning excrement cans every day. Wasn't long before another Marine suggested that the last man to use the 'commode' before it was completely full be required to place a grenade, spoon down and pin pulled, into the canister on top of the excrement, screw the top down tight and pitch it off the hill, which was steep. The canister would bounce a good distance down. Every once in a while, late at night, we'd hear an explosion and screams from down below."

When the morale took a drop, one private first class wrote a letter to his pastor back home. It started "Operation We Care," which resulted in an abundance of "We Care" packages arriving at 881S.

"We also received gin and vodka in plastic baby bottles. A note from one donor, a Korea veteran, said he remembered what a little 'joy juice' could mean to front-line troops, and that he'd used plastic baby bottles because they wouldn't break with rough handling. I recall one load of incoming mail; several days' worth, where letters and packages were riddled with shrapnel and soaked with whiskey from a broken bottle in one of the 'We Care' packages. (Chocolate chip cookies soaked in bourbon weren't that bad.)

"There was a deli in Wantaugh, N.Y., that sent us neat packages including whole salamis, other smoked meat and 'joy juice.' "

Dabney explained the "juice" wasn't a problem because "with 250 to 400 men, even large packages had only enough for about one sip per man. Morale did improve because troops realized folks back home cared."

Morale-boosting events weren't limited to actions by the people back home. It started in February and continued every day. "Three Marines would race from the bunker to a 15-foot radio antenna. Two of them would raise our nation's colors, then stand at attention, while the third sounded a rusty rendition of the 'Call to Colors' with a battered bugle. We were never without volunteers for this ceremony. They were proud of themselves and our flag and were willing to get shot at to raise it.

"At night this process was reversed as we retired the colors. Often the retired flag was folded, packed and shipped to the family of a Marine slain on the hill. We had a substantial stockpile of flags sent to us by people all over the country."

"He also devised an early warning system whereby NVA artillery and [rockets firing] from the west were immediately reported by lookouts to the Khe Sanh Combat Base, giving exposed personnel a few life saving seconds to take cover, saving countless lives, and facilitating the targeting of enemy firing positions."

Riflemen burrowed in on the crest of Hill 881S could, through eyes bloodshot and raw from dirt and fatigue, see and hear North Vietnamese artillery and rockets coming up from the hills and valleys of Laos and the Demilitarized Zone. The big artillery rounds going over sounded like squirrels running through dry leaves.

It is an eerie emotion watching large artillery rounds flying overhead. There is awe and much fascination that such large objects can be hurled so far and so accurately. There is death, not some apocalyptical horseman, but the real knowledge that death is riding a rocket and that lives may in seconds end for men who are remarkably like you and only want to live and do their duty.

"For what it is worth, the folks in the Khe Sanh COC [combat operations center] never realized how the NVA artillery was emplaced and employed," Dabney would later comment. Hill 881S had been chosen as a regimental outpost for sound tactical reasons. From the hill, Marines could observe the NVA gunners shoot off their rockets, usually in sheaves of 50 firing simultaneously from several sites toward Khe Sanh. This permitted Dabney's Marines to give the main base about a 10-second warning to sound the alarm and for the Marines there to take cover. While unable to suppress the rockets because of their sheer volume, Dabney's Marines could and did take countermeasures. Dabney had noted the NVA regularly used the same sites over and over, so he employed his mortars and 106 recoilless rifles against them "at night" while they were setting up, sometimes producing secondary explosions.

"Colonel Dabney repeatedly set an incredible example of calm courage under fire, gallantly exposing himself at the center of every action without concern for his own safety. Colonel Dabney contributed decisively to ultimate victory in the Battle of Khe Sanh, [which] ranks among the most heroic stands of any American force in history."

In the end, Khe Sanh and its surrounding outposts were no Dien Bien Phu or even the Alamo. The North Vietnamese, pummeled by artillery and air power, abandoned their siege. Khe Sanh had earned its own place in American history.

**********************************

I think you will enjoy reading the account of Bill's being presented with the Navy Cross at his alma mater...

Thirty-seven years later, Dabney watched VMI's brigade of cadets pass in review before him. Lieutenant General H. P. "Pete" Osman, Deputy Commandant for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, who as a company grade officer had served with Dabney when he was a major, presented the Navy Cross, saying, "Well-deserved, if maybe a couple years late."

LtGen Osman also said that Dabney is a positive man who "still sees the glass as half full."

Dabney stood to address those who had traveled or been mustered to honor him. He introduced the VMI cadets to 37 fellow Marines who had served with him on Hill 881S. As they stood up in Jackson Memorial Hall (named for Civil War Confederate LtGen Thomas J. "Stonewall" Jackson), Dabney said of his men: "These are the citizen-soldiers of the '60s who fought against the same general [Vo Nguyen Giap] who overwhelmed the French at Dien Bien Phu. And [it is these men] who, by enduring, triumphed. It has been the greatest honor of my life to have served with these men in battle."

The cadets of VMI, a school that embodies military discipline and the tradition of the citizen-soldier, and has for more than 173 years graduated some of the nation's best military officers of whom Dabney is one, listened.

"Many of you will lead the citizen-soldiers of this nation in Iraq and Afghanistan. You will find them, as I did, awesome in their courage and determination."

Later they all talked long into the night and heard of other men such as Second Lieutenant Thomas D. Brindley, Corporal Charles W. Bryan, 2dLt Michael H. Thomas, who earned Navy Crosses, and Cpl Terry L. Smith, who earned the Silver Star, all posthumously on Hill 881S, all "awesome in their courage and determination."

You may also enjoy Bill's address that day...

Over the years, I have reflected on the performance of the Marines who defended Hill 881S during the Siege of Khe Sanh. There were many bad days, a few good ones and an occasional uneventful one, but the chief characteristic of the situation in which the Marines found themselves was its constancy.

There was never a climactic day or event. Rather, from 21 January through 17 April 1968, the threat to life and limb remained essentially unchanged. The dangers were greatest during helicopter operations because those offered the most lucrative targets to the enemy's gunners. The potential for catastrophe, however, was greatest at night or during the frequent foggy weather when we could not see to detect the enemy's approach or to bring our massive supporting fires to bear against him. That potential took a psychological as well as a physical toll. To stand in a trench for eight hours on a given night without relief, in total darkness, in a fog so thick that even a magnesium flare could not pierce it, all senses focused on detecting any sound, any smell, any hint of movement to the front, was trying in the extreme to the Marine required to do it. To require all hands do so nightly for three months was to stretch the limits of resolve. Early on, a Marine approached the company gunnery sergeant tentatively in the trenchline one ink-dark night. He was nervous and ill at ease, but said he felt a duty to speak out. The gunny assured him that he could speak freely, to which he replied that he was loathe to admit that he knew what it smelled like, but that he'd been smelling pot in the wind coming toward the trench line from the north, and that the smell was getting stronger. Relying on his instincts as to the location of the source, we fired over one thousand rounds of mortars and mixed-fuse artillery.. We were not assaulted. There was never thereafter any reticence to report observations or hunches.

We all knew that if the North Vietnamese assaulted there was no possibility of reinforcement or withdrawal. Aside from the preplanned supporting fires, we were entirely on our own. The Marines had daily opportunities to take the measure of their enemy. He was brave, he was disciplined, and he was not suicidal, so they knew that he would assault only when he was reasonably confident of success, and with adequate strength They were aware that both neighboring positions had been penetrated by assaults. They also knew that if wounded, they would be evacuated to a medical facility only when and if the weather broke and the helicopters could fly - that there was little their Corpsmen could provide save comfort and some morphine to ease their pain.

Every man has a psychological limit, and a few broke - a very few. Even those men tended when they broke to manifest it by aggression rather than by withdrawal; to charge out through the defensive wire armed to the teeth, determined to destroy the enemy single-handed, or to become fatalistic and take irrational risks. A few were weak in contrast to their comrades. Command intervention was rarely necessary in those cases, for their fellows Marines seemed to sense the solution appropriate to the individual; be it persuasion, example, or, in extreme cases, physical correction, and even the last was only as direct as was required.

The Uniform Code of Military Justice was useless in the circumstances. A company commander was limited to fining a Marine one week's pay or withholding two weeks', or to restricting him for two weeks. Since most men had not been paid in several months and all were surrounded by quintuple concertina wire and a North Vietnamese Army regiment, those penalties bordered on the absurd. Any meaningful punishment required that the offender be removed from the hill to appear before the battalion commander at Khe Sanh or, for the most serious offenses, before a court-martial convened at some remote rear area base. All hands knew that both Khe Sanh and the Da Nang brig were infinitely safer than the hill, and there were even two or three who actively sought courts-martial. To refer them for such and therefore to send them off the hill was exactly what they wanted so was not an option. It was also unnecessary. The staff non-commissioned officers were superb at correcting those few quickly and privately with traditional methods, and the offenses were never repeated. The troops were equally effective at correction, as when a replacement or returnee from treatment for wounds would bring marijuana or some other drug back with him. He quickly discovered that his fellows would not tolerate drugs on the hill. Their lives depended utterly on the alertness and acuity of their comrades, and their response to those who had or used them was immediate, violent and wholly effective.

Although the siege was contemporary to the peak of racial strife in America, there were no racial tensions on the hill. On the occasion of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination, a black NCO asked that the flag be flown at half-mast for a day. He was told that his sentiment was understood and shared, but that the flag was both critical for morale and a gesture of defiance to the enemy, and its lowering was therefore inappropriate. He agreed, withdrew his request, and volunteered for the flag raising detail the following morning. It did not take long on that hill for a man to determine the worth of his trench mate, and once he did, all other considerations became irrelevant. I have heard it said that no environment involving Americans can exist without racial tensions. I disagree.

Heroism was routine. The helicopter zones were always "hot", and given that the enemy's weapon of choice to attack them was the 120mm mortar, deadly. Most dangerous were the medical evacuation missions It took time to carry badly wounded men from cover to the helicopter and then return to cover, and the mortar rounds were often already announced as being "on the way". Yet there was no occasion when men had to be ordered to carry stretchers. To the contrary, it was often necessary to restrain too many men from lending a hand and exposing themselves unnecessarily. A Marine had his foot blown off, and by the time the Corpsman got to him, he had lost considerable blood. The Doc, exposed and under fire, was determined to save him, but because of weak pulse and low blood pressure, could not find a vein to start an I.V. The man had given up and was moaning weakly in self-pity. The Corpsman slapped his face violently and repeatedly, provoking such anger in the man that his adrenaline kicked in, whereupon the Corpsman found a vein and saved him.

There were moments of humor. A Marine manning an observation post had a spent rifle round ricochet up from the ground and hit the bottom button of his fly. The button happened to be resting against the head of his penis. The button absorbed the impact and there was no penetrating wound, but within an hour of his being hit, his penis had swelled to the size of a salami and his testicles to the size of tennis balls, both turning a deep purple. A radio conference with a physician down at Khe Sanh established that his wound was not life-threatening and therefore did not justify an emergency medical evacuation with the consequent risk to the helicopter. The physician stated that he could do little more than ease the pain, which the corpsmen on the hill could do as well, or amputate, which the Marine would probably not want, and he said that the swelling would eventually subside. For the next several days until we landed a helicopter for a more serious casualty and could get him out, the Marine wandered the trenches disconsolately in helmet, flack jacket and boots, walking like a drunken cowboy to avoid any contact with his injured parts. The jokes of his comrades - about his future prowess, his potential attractiveness on R & R, the fashion statement he was making - were hilarious, albeit unprintable.

There was also frustration. The lack of a secure means of communications between the hill and Khe Sanh meant that we and the base had to be guarded in what we said, since we had to assume that the enemy was listening. For us on the hill, that meant that although we could report enemy activity, we could not report our analysis of it, nor could we report the shortcomings of supply, support and communications that constrained our tactics. In several instances where the needs were critical and immediate we transmitted in Spanish, and sometimes even in song. The inability of the base to send secure messages to us was even more limiting. We were, after all, the regimental outpost, and we found ourselves, by the nature of the campaign, in the midst of the enemy. We rarely got any feedback either to our frequent reports of enemy activity or describing the successes that resulted from those reports. This was critical to us. The troops observed and reported at considerable risk to themselves, yet the most frequent question they asked was, "Hey, skipper, are we doing any good?" That lack of positive reinforcement was both frustrating to the officers and destructive of the troops' morale, irrespective of the tactical justification for it. One night in mid-February, sensors detected enemy units marshalling to attack the hill in overwhelming force. The regiment fired a massive and prolonged artillery barrage to break up the attack, but we were never even told the attack was coming because the very existence of the sensors was so highly classified.

We were probably as ready as we could be to repel it in close, but we also had ample indirect fire weapons and ammunition to slow it at a distance had we been told it was imminent and from which direction it was coming, and we had a far more intimate knowledge of the terrain that the enemy had to negotiate than did the regiment. It was as though we had been sent to detached duty on another planet. We were ignorant of virtually everything that was happening beyond our own little world, and the troops felt that ignorance keenly.

The troops would occasionally capture NVA soldiers, either because they surrendered voluntarily or because they blundered into our lines inadvertently in the night or fog. Initially, we reported those captures immediately to the base, which promptly sent a helicopter up to get them. We assumed that the value of the POW justified the risk to the helicopter and to ourselves in getting him out. We also assumed that the captives were from the units surrounding us and therefore had information of immediate tactical value to us. After two or three instances of sending prisoners down and getting no feedback from their interrogation, we began delaying our reports of capture a few hours so we could interrogate them ourselves. Most talked willingly, and our two Marines who had been to Vietnamese language school could, although a long way from fluency, learn enough to help us with targeting and tactical dispositions.

Personnel accountability was a nightmare. Turnover in the trenches approached ninety percent, which meant that many men were virtually unknown to their fellows, and the restrictions on movement imposed by the enemy's fires meant that the personal interactions normal in a unit were often impossible. Replacements would be dispatched from the rear, get hit while still on the inbound helicopter, remain aboard, and be evacuated to a medical facility. Our rear would insist we had them when we had never seen them. One Marine managed, through bad luck, a total of two day's service in Vietnam. Although we were careful to record every man who boarded a helicopter so that if it was downed we'd have an accurate manifest, we were sometimes thwarted. In one instance, a stretcher bearer from a platoon distant from the zone was hit in the helicopter as he put down his stretcher and was retained aboard by the crew chief. The helo immediately launched and flew directly to the hospital ship offshore. In the confusion typical of a zone under fire, exacerbated by the fact that the original casualties had resulted from hits in the same zone and that the chase bird had landed unbidden within a minute to pick them up before we had time to organize the zone, he had not been missed, and his name did not appear on the manifest. We carried him as missing-in-action for two weeks until a platoon buddy received a postcard from him, with a return address of St. Alban's Naval Hospital in New York, describing what had happened and asking him to secure his personal effects.

Thirty-eight Marines or Corpsmen died on or near the hill and nearly two hundred were wounded, not including aviation casualties whose numbers, being reported separately, were unknown to us. Seven helicopters were shot down, yet we never called for a medevac that didn't come, weather permitting. None of these losses occurred in a single pitched battle, but rather in discrete incidents scattered over the course of the siege. Incoming was constant, and although we learned to cope with it to a point, a lucky round in a trenchline or active medevac zone was just as deadly in April as in January. Through it all, the troops did their duty. They stood their watches, flew their aircraft or serviced helicopter zones, manned outposts, engaged the enemy and raised the flag as zealously at the end as at the beginning. They were never asked to stand back-to-back against the flagpole with fixed bayonets, but rather to endure. By enduring, they triumphed. They were magnificent!

(Refusing a microphone, Colonel Dabney addressed those in attendance with a strong voice that reverberated throughout Jackson Memorial Hall as follows:)

Will those who served on Hill 881 South or flew in support of it, and those who are here to represent the men who died doing so, please stand and face the audience. (39 Marines and one Navy Corpsman sitting in the front rows of Jackson Memorial Hall stood and faced the capacity crowd of approximately 1,200. Immediately thereafter, all remaining guest stood and applauded the Warriors until Colonel Dabney had to gesture for silence. The Warriors remained standing as Colonel Dabney continued) Thank you.

Ladies and gentlemen, these men standing before you, and the the Marines and Navy Hospital Corpsmen, living and dead, whom they represent, are the men who, for 77 days at Khe Sanh, held the hill and poured hot steel on a determined enemy. The same forces under the same general besieged Khe Sanh as had overwhelmed the French at Dien Bien Phu. At Khe Sanh, they were faced by these men, and they quit and faded away. These men did their duty and endured - Stonewall Jackson would have called it resolve - and by enduring, they triumphed.

It is the greatest honor of my life to have served with these patriots in battle. I wear this decoration only sym- bolically, as their commanding officer. It is these men who earned it.

Gentlemen, we salute you!(The Warriors took their seats to another rousing round of applause.)

Will the VMI Corps of Cadets please rise. (All seats remaining vacant after invited guests were seated had been occupied by cadets.)

Our generation - these men who just stood before you - came home from war to a nation not much disposed to honor the nobility of their service. Today, as Pete said a few years late, you gave us our parade. Thank you! (Audience and Warriors applauded the cadets)

Many of you will soon shoulder the responsibility of command leading the citizen soldiers of your generation. Eight of your number have already given their lives in the cause of freedom in Iraq or Afghanistan. Should you be called upon to take America's patriots in harm's way, you will find awesome, as I did in my time, their courage and determination. The experience will become the signal moment in your lives. We wish you God speed, and we salute you. (Another round of applause with the loudest and most robust coming from those 40 men in the front rows of Jackson Memorial Hall.)

The official party departed the stage with Colonel Dabney again in his wheel chair assisted by his wife Virginia. He stopped in the center isle of the hall next to those first front rows, and once again in a voice heard throughout the hall said, "Follow me men!" And once again they did.

(Michael F. Cullen, a Lance Corporal who served in the 1st Platoon of India Company later said, "We would have followed you to Iraq through the gates of Hell!")

Read More about Hill 881s ---- http://www.hmm-364.org/warriors.html