The Man Who Inspired the Black Lion Award

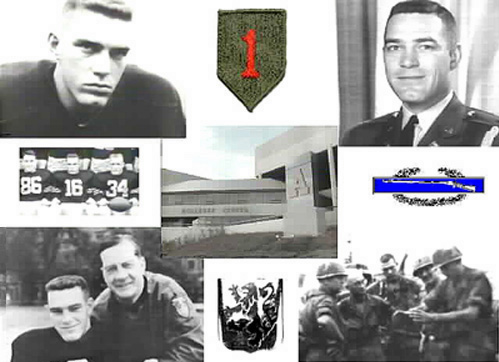

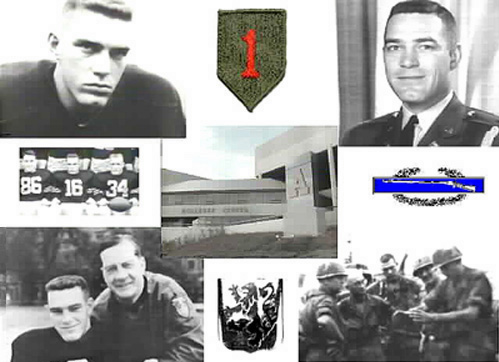

(Collage of photos and memorabilia lovingly provided courtesy of Dave Berry and Tom "Doc" Hinger)

The Man Who Inspired the Black Lion Award

(Collage of photos and memorabilia lovingly provided courtesy of Dave Berry and Tom "Doc" Hinger)

(Clockwise from Upper Left: Don Holleder, All-American end; The 1st Infantry Division patch; Major Donald W. Holleder; Combat Infantryman's Badge; A photo taken on the morning of the Battle of Ong Thanh and printed from film recovered after the combat photographer, Verland Gilbertson, was killed - Don Holleder is in the center; The symbol of the Black Lions; Army's Colonel Earl "Red" Blaik and the man he chose to become his quarterback; Don Holleder, #16 in the front row of Army's 1955 team picture; MIDDLE: The Holleder Center at West Point)

By Hugh Wyatt

Don Holleder's senior season at West Point is a story of unselfishness. It is a story, too, of leadership - of a coach who needed a leader for his team, and the player who wanted to be that leader, even at the cost of personal glory. It is a story of the trials the coach and his leader faced together, and of their ultimate vindication.

Led by senior quarterback Pete Vann and junior All-America end Holleder, plus four outstanding runners in Tommy Bell, Bob Kyasky, Pat Uebel and Mike Ziegler, the Cadets of West Point had led the nation in total offense in 1954, finishing 7-2 and ranked seventh in the nation in the AP poll.

But with Vann graduated, Army's Coach Earl Blaik found himself facing the 1955 season without a proven quarterback. Although there were two upcoming first classmen (seniors) returning at quarterback, their playing time had been limited, and Coach Blaik evidently saw a need to strengthen the position. His solution, after considerable deliberation, was to approach Holleder, the returning All-America end, about making the switch to quarterback.

On the surface, it did not appear to be a wise move. Holleder, though a gifted athlete, had not only never played quarterback; in high school and college, he had never played in the backfield. He had another serious limitation as well - he had a strong arm, but he couldn't pass. "I knew," the coach recalled in his autobiography, "that in the one season of eligibility he had left, he never could possibly develop into a superior passer, but he might do well enough to get by."

Nevertheless the coach felt that Holleder had other qualities that more than compensated for what he lacked. "On the plus side," he noted, "Holleder was a natural athlete, big, strong, quick, smart, aggressive, a competitor. I knew he could learn to handle the ball well and to call the plays properly. Most important, I knew he would provide bright, aggressive, inspirational leadership."

After proposing his plan to an astonished Holleder, Blaik told him to go back to his room, think it over, and come back the next day with his answer.

After his first morning class the next day, Holleder met with Blaik as agreed on. He told Blaik that he hadn't slept much.

Then and there, Don Holleder, the All-American for whom Blaik had predicted brilliance had he remained at end, announced his willingness to make the switch for the good of his team - a sacrifice of personal glory almost unthinkable to the athlete of today.

As Blaik remembered, "He said that if I thought he could do the job, he was willing to make a try at it."

In his 15 years at West Point, Blaik had made important personnel moves, but none so highly publicized, and certainly none so controversial as this one would become. In the past, it had been generally acknowledged that Blaik knew what he was doing and that results would prove him correct; but this move was greeted with skepticism in all quarters. In 1955, Army was still a very high-profile national football power, and once Blaik's decision was announced, his judgment was questioned on the radio, in the newspapers, and at West Point itself. There were even those who dared to suggest that, at the age of 58, Colonel Blaik might be losing his faculties.

And almost from the start, the skeptics appeared to be vindicated, when Holleder broke his ankle a week into Spring practice and missed valuable learning time.

Injuries and graduation had required other personnel switches as well - so many, in fact, that only one Cadet would wind up start ingthe 1955 season at the same position he had played in 1954. The running back corps, originally expected to be a strong point, was depleted when Kyasky broke his collarbone in the opening game, and Ziegler was sidelined by disciplinary infractions.

But despite question marks at several spots, the Cadets opened the season with a pair of victories, one of them a 35-6 win over Penn State. Next , though, came games against two powerhouses, Michigan and Syracuse, and when Army lost them both, the criticism of Holleder began to mount.

Michigan, whom the Cadets had defeated 26-7 the year before, shellacked the Cadets, 26-2. The major reason for the loss could be found in the turnover statistics - Army fumbled 11 times, and lost the ball seven times - but when a team fails to score offensively, it is easiest to point the finger at the quarterback, and Holleder hadn't helped his own cause with his play. He completed just one pass in eight attempts for just 15 yards. (And even that lone completion resulted in a turnover, when the receiver fumbled at the end of the play.)

On the Monday morning following the Michigan game, the Academy Superintendent , Lieutenant General Blackshear Bryan, stopped by Blaik's office to convey his concerns about the quarterback situation. The idea of a college president conferring with the head football coach over such matters would be unheard of anyplace else, but first of all, Coach Blaik's contract called for him to report directly to the Superintendent; and second of all, at a service academy, at an institution devoted to leadership, the entire post takes an active interest in the football program as an important part of that training. And a great many of West Point's officers and cadets had grown critical of Holleder's leadership, and much of their criticism had made its way to General Bryan.

Blaik had a good relationship with General Bryan. He heard him out and then tossed the ball right back, to him. "You tell me," he challenged the Superintendent. "If not Holleder, then who?"

When the Superintendent confessed that he had no answer, Blaik then asked him to help Holleder's cause by voicing his support - openly. Blaik, a West Point graduate himself, knew quite well that once others knew where the Superintendent stood on the matter, criticism of Holleder would subside.

But only after the Superintendent had left the office, and Holleder had arrived for his regular Monday meeting with the coach, did Blaik become aware of just how destructive the criticism of his quarterback had become.

Holleder told Blaik that on his way to the meeting, he had overheard a conversation between two other Cadets walking closely behind him. Unaware of who he was, they were discussing Holleder's play at quarterback; it was their opinion that while Holleder had been an excellent end, either one of them would have made a better quarterback.

Putting an arm around his quarterback's shoulder, Blaik assured him that he still had his coach's confidence. "It doesn't matter what anybody else thinks or says around this place, " Blaik told young Holleder. "I am coaching this Army team. And you are my quarterback!"

Blaik recalled seeing Holleder's eyes start to fill with tears. Holleder told Blaik that he had given a lot of thought to what he had just heard the two cadets saying about him, and that as he had climbed the stairs to the coach's office, he was prepared to offer to go back to end.

But in spite of the criticism, he told the coach, he really wanted to remain at quarterback - he wanted to lead the team. "I was praying you would say just what you have said," he told the coach. "I'll show everybody around here that I can do more for the team at quarterback than I could anyplace else."

Unfortunately, next up was Syracuse, and the continued lifelessness of the Army offense and the running of future NFL Hall-of-Famer Jim Brown resulted in a13-0 Orangemen victory. With the Cadets' second straight offensive shutout, the criticism of Holleder surged. It subsided somewhat as the Cadets soundly defeated Columbia and, with Holleder throwing for three scores and running for the fourth, downed a good Colgate team 27-7, but it resumed in full force the next week, as Yale upset the Cadets, 14-12 before 70,000 in the rain and mud of the Yale Bowl.

A 40-0 win over a poor Penn team did little to silence the critics, as the Cadets began preparations for the season finale against powerful Navy.

The Midshipmen were 6-1-1 going into the Army-Navy game, and they were led by quarterback George Welsh (later to become head coach at Navy and at Virginia). Welsh, the hero of the previous New Year's Day's stunning 21-0 Sugar Bowl win over powerful Ole Miss, was leading the nation in passing.

The night before the game, traditionally played in Philadelphia, the Army team, cloistered as was its custom at a suburban coutry club, gathered for a few pre-bedtime words from Coach Blaik.

"I've grown weary, " he told his players, "of walking across the field to offer congratulations this year to Bennie Oosterbaan of Michigan, Ben Schwartzwalder of Syracuse, and Jordan Olivar of Yale. Now, I'm not as young as I used to be, and that walk tomorrow, before one hundred thousand people, to congratulate Eddie Erdelatz (Navy coach) would be the longest walk I've ever taken in my coaching life."

Blaik recalled a few moments of absolute silence. Finally, though, someone spoke. "Colonel," a voice said, "you are not going to take that walk tomorrow!" The voice was Don Holleder's.

But the next day, Holleder's words began to seem like an empty promise, as Navy took the opening kickoff and drove 76 yards to take a 6-0 lead.

Controlling the ball for most of the first half, Navy twice threatened to put the game away with two more long drives. Twice, though, the Cadets' defense stopped them at the Army 20. Holleder , playing both ways under the rules of that time, had a hand in both stops, the first time hitting a receiver so hard he dropped a fourth-down pass, and the second time falling on a Navy fumble.

Despite being frustrated offensively for most of the first half, the Cadets did finally manage to put together a drive of their own in the closing minutes, but they ended up on the Navy one-yard line as time ran out.

Undiscouraged by that failure, though, the Cadets seemed to gain confidence from the near-miss, coming out and driving 41 yards for a third period touchdown and, following the successful conversion, a 7-6 lead.

But the Midshipmen roared right back, with Welch driving them 72 yards to the Army 20. Once again, though, Navy missed a great scoring opportunity, losing the ball on a fumble.

And then, as if to demonstrate that wars are still fought and won by foot soldiers, the Army running game took over, as the Cadets drove 80 yards for another score, and then held on tenaciously for the 14-6 upset win.

Despite the aerial heroics of Navy's Welsh, who threw 29 times and completed 18 for 179 yards and a touchdown, the contest was won by the infantry. Army finished with 283 yards total offense - all of it on the ground. Of the two Army passes thrown, one was intercepted and the other fell incomplete.

"There hasn't been anything like it since the ancient days of the flying wedge," marvelled the New York Times' Arthur Daley.

General Douglas MacArthur, a long-time supporter of Army football and of its coach, sent Blaik a congratulatory telegram, indicating that he was well aware of the problems the coach and his quarterback had overcome:

NO VICTORY THE ARMY HAS WON IN ITS LONG YEARS OF FIERCE FOOTBALL STRUGGLES HAS EVER REFLECTED A GREATER SPIRIT OF RAW COURAGE, OF INVINCIBLE DETERMINATION, OF MASTERFUL STRATEGIC PLANNING AND RESOLUTE PRACTICAL EXECUTION. TO COME FROM BEHIND IN THE FACE OF APPARENT INSUPERABLE ODDS IS THE TRUE STAMP OF A CHAMPION. YOU AND YOUR TREMENDOUS TEAM HAVE RESTORED FAITH AND BROUGHT JOY AND GRATIFICATION TO MILLIONS OF LOYAL ARMY FANS.

Jesse Abramson, in the New York Herald-Tribune , had the last word on the move of Holleder to quarterback: "Never," he wrote, "were a coach and a player subjected to so much criticism on a matter which involves a basic item of coaching: proper appraisal of an individual's ability to handle the job assigned to him."

For Holleder, who had passed up a sure repeat spot as an All-America end because he was needed elsewhere, the win over Navy was his vindication. As he had promised, his coach did not have to make the loser's walk across the field to offer congratulations to the Navy coach.

|

|

A victorious Army team celebrates the epic 1955 win over Navy. Don Holleder is at right, next to the Academy Superintendent, Lt. Gen Blackshear Bryan. From left, Dave Bourland, Coach Earl "Red" Blaik, Russ Mericle, Captain Pat Uebel, Dick Murtland, LTG Bryan, Pete Lash, Bob Kyasky (partially hidden), Don Holleder, Unidentified player, Loren Reid, and trainer Rollie Bevan (whose face is covered by his clapping hands) (Photo and identifications courtesy of Tom Kehoe, West Point '57) |

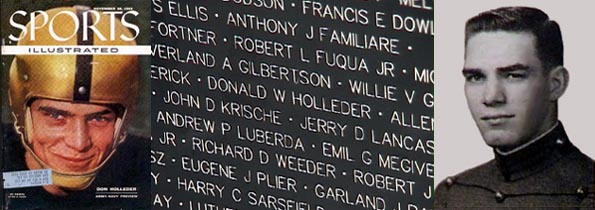

Ironically Don Holleder, the consummate team player, received the ultimate in individual recognition when he made the cover of that week's Sports Illustrated.

But now he had a military career ahead of him. Speaking for both the Superintendent and himself, Coach Blaik stated in 1960 that it would not surprise either of them if Don Holleder were to go as far as a military leader as his "selflessness, courage and inspiration" had taken the Army football team.

After graduation from West Point, Holleder went on to become an outstanding officer. Following Infantry Officers School and Paratroopers School, he spent two years in Hawaii, followed by a 3-year tour of duty as an assistant coach at West Point.

Who will ever know how far he might have gone as a military leader?

With America becoming more deeply involved in Vietnam, he volunteered to do a second tour of duty there.

On October 17, 1967, as the West Point team prepared to meet Rutgers, Major Donald W. Holleder, the personification of the selfless leader and team player, the man who sacrificed personal glory for the good of his team, the man who persevered and ultimately prevailed despite the odds, the man who represented the very best America has to offer, was cut down by a sniper's bullet as he hurled himself into enemy fire attempting to rescue wounded comrades ambushed at Ong Thanh, some 40 miles north of Saigon. 57 Black Lions died with him that day and two are still Missing in Action. Don Holleder was 33 years old, married and the father of four.

Army medic Dave Berry told the story best: "Major Holleder overflew the area (under attack) and saw a whole lot of Viet Cong and many American soldiers, most wounded, trying to make their way our of the ambush area. He landed and headed straight into the jungle, gathering a few soldiers to help him go get the wounded. A sniper's shot killed him before he could get very far. He was a risk-taker who put the common good ahead of himself, whether it was giving up a position in which he had excelled or putting himself in harm's way in an attempt to save the lives of his men. My contact with Major Holleder was very brief and occured just before he was killed, but I have never forgotten him and the sacrifice he made. On a day when acts of heroism were the rule, rather than the exception, his stood out."

In 1985, Don Holleder was installed in the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame. That same year, West Point's indoor sports facility was dedicated and named the Donald W. Holleder Center in his honor.

In 2001, with the approval of his widow, Mrs. Caroline Ruffner, the Black Lion Award was instituted, to honor Major Don Holleder and the men of the Black Lions.

***************

Author's note: As a football coach, it was a highly emotional moment for me when I visited The Wall in Washington, D.C. a few years ago. Undoubtedly feeling the same emotion thousands before me had felt, I hoped that somehow the name I was looking for wouldn't be there - that it was all a mistake. But, dear God, there it was - panel 28E, row 25 - Donald W. Holleder.

***************

Further note: I have been privileged as a result of my research into the life of Don Holleder to have made the acquaintance of two men who were on the scene on that fateful day, Tom Hinger and Jim Shelton. It was through my association with those men that the idea of the Black Lion Award was born.

December 18, 1998Sir,

While surfing the net I came across your page, and the tribute to Major Holleder. I am a survivor of the battle in which he lost his life, in fact he died in my arms. A visit to West Point would not be complete without a visit to the Holleder Center. For those of us that were lucky enough to survive the Battle of Ong Thanh, the Center is a tribute to all our fallen comrades.

Thank you,

Tom Hinger

*****************

December 21, 1998Dear Coach Wyatt:

A friend of mine , Tom Hinger, who held Don Holleder as he died in the jungle in Vietnam on 17 Oct 1967, introduced me to your web site. In 1953 I went to the University of Delaware as a center and linebacker. I played for Dave Nelson for 4 years. Mike Lude was our line coach. Mike later went on to become AD at UW with Don James, and you must know Mike. I was a guest of his at the Waldorf when Don Holleder was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. In 1955 we went up to West Point and scrimmaged Army. Don Holleder was the quarterback, and was a load to bring down. He couldn't throw, but he loved to belly to the fullback then keep the ball.Our defense was lousy (I was defensive captain) but prior to that scrimmage we hadn't worked a day on defense. Riding up the New Jersey turnpike in a bus to West Point Mike was telling me to call the defenses we had worked on in spring practice. None of our guys remembered any of those stunts. We sat in an Eagles 550. Army was taking big splits and we ended up using a goal line defense to shoot the gaps. Needless to say, a Dave Nelson (and Tubby Raymond) football team will always be an offensive minded ball club. We did score about 6 TDS in the scrimmage. It was a great experience for us. Twelve years later I found myself in an infantry battalion in Vietnam as S3(Operations officer) and Don Holleder was our brigade operations officer. I spent many hours laughing with Don over that football scrimmage.He was an indomitable man--courageous and bullheaded. When he saw those wounded men on the ground he dived into the middle of the fray and was immediately cut down by a sniper. I was later one of the guys who helped to identify his body, along with too many others. I couldn't believe that he could be dead--how a guy as powerful and full of strength could be so lifeless. It was a very sad day--unforgettable. Each year a small group of us trek up to West Point on a date near to 17 Oct to remember Don and our other comrades that were lost that day. In spite of the sadness we always have a good time. Tom Hinger and I are very close--with a mutual experience which transcends most everything else. I want to wish you continued success with your Double Wing system.

God bless America.

Jim Shelton

If you enjoyed reading about Don Holleder, you will enjoy reading about the fabulous career of his coach, the great Colonel Earl "Red" Blaik

See Also ARLINGTON CEMETERY/DON HOLLEDER