JORDAN OLIVAR - AN AMERICAN SUCCESS STORY

By Hugh Wyatt

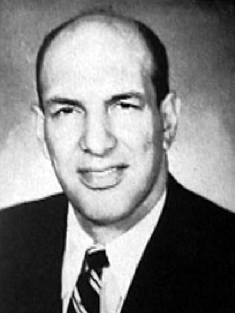

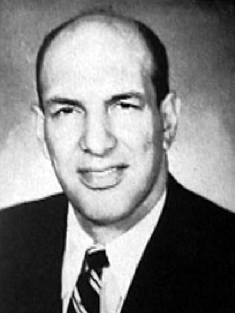

Jordan Olivar's life was an American success story. Considering the fact that he never played high school football, he didn't do too badly as a coach. His coaching career took him from a tiny New Jersey high school to one of the nation's most prestigious Ivy League universities. In the process, he crossed the country twice. While on the West Coast, his team, Loyola of Los Angeles (now Loyola-Marymount), and his quarterback, Don Klosterman, led the nation in passing yardage; suddenly, though, following the 1951 season, Loyola discontinued football, and he hired on as a part-time assistant at Yale. But when the Elis' head coach abruptly quit in midsummer to pursue an opportunity in the then-new television business, Olivar unexpectedly found himself offered the head coaching job. He accepted, and in 12 years at Yale, became known as one of the chief developers and proponents of the Belly-T offense. His book, "Offensive Football - The 'Belly' Series", was written in 1958, but it is up-to-date in its thinking and is highly useful to anyone considering using the offense.

For much of the following, I am indebted to his son, the late Harry Olivar, a college teammate and classmate.

Jordan Olivar was born Giordano Aurelio Olivari in 1915, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Italian immigrants. His father had jumped ship in New York, and later, Coach Olivar would enjoy telling people that his father was an early illegal alien. His father supported his family waiting on tables, and picked up a little money on the side as a boxer.

Jordan Olivar was born Giordano Aurelio Olivari in 1915, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Italian immigrants. His father had jumped ship in New York, and later, Coach Olivar would enjoy telling people that his father was an early illegal alien. His father supported his family waiting on tables, and picked up a little money on the side as a boxer.

Italian was the language spoken in the Olivari home. During Prohibition, he helped his father make wine, recalling later how he hated having to stomp the grapes in his bare feet.

From Brooklyn, his family moved to Staten Island, where he attended Curtis High School, and graduated in 1930. He played high school soccer and baseball, but was ineligible to play high school football - there was a minimum age requirement, and he was never old enough.

Although he graduated first in his class, college was not an option. It was 1930 and America was hard-hit by the Depression. Through friends, he managed to find a job in a men's gym, sweeping floors and picking up towels, and occasionally earning tips by playing handball against members when no other opponents were available. In time, members began to request him as an opponent, and, sometimes playing as many as 30 games a day, he became rather good.

So good did he become, in fact, that as his son, Harry, told it, "He would sometimes bet on the games, giving his opponent as much as 18 points to start (game is 21), as long as he could serve first. To score a point you have to be serving, so his opponent would have to win twice - first breaking Dad's serve, then making a point on his own serve. Sometimes, if an opponent was not very good, Dad would just offer to play with his feet - which the opponent would take him up on, not knowing he was a soccer player."

One day, a wrestler showed up at the gym in search of a workout opponent, and saw young Olivar at work. Olivar was a big kid, 6-4 and beginning to fill out, and the wrestler said, "Hey, come here, kid! Let's go a few rounds!"

Things went as one might expect, until finally young Olivar, tired of being tossed around, suggested a game of handball instead.

Things went differently on the handball court, and the wrestler, run ragged and badly beaten, said, "Hey, kid - you're a pretty good athlete. How'd you like to play football? I know some people - I can get you a scholarship at either Notre Dame, or Fordham, or Villanova."

Young Olivar gave it a little thought, and said "Villanova!" Later in life, he would explain his logic: Notre Dame was the number one team in the country, and he might not be able to play there; and Fordham was close by, in New York, where they would have known that he'd never played high school football.

He never regretted his choice. As he would tell it later, for a kid from the streets of New York, going to Villanova with its green, leafy campus, where you got to eat three meals every day and all you had to do was go to classes and play sports, was like going to heaven.

Although he had never played in a game of football until he arrived at Villanova - on a football scholarship, yet - he wound up starring on some of the Wildcats' greatest teams, playing first for Harry Stuhldreher, one of Knute Rockne's legendary Four Horsemen, and then for Maurice "Clipper" Smith, another former Rockne player. For some reason, Coach Stuhldreher referred to him as "Olivar" and to his teammate Alex Belli as "Bell," and both men wound up anglicizing their names.

In his senior year, Villanova finished 8-0-1, outscoring opponents 185-7 and shutting out eight of them, and he was named co-MVP. The only blemish on the Wildcats' record was a 0-0 tie with Auburn. As an indication of Olivar's football intellect (and Clipper Smith's resourcefulness) he was entrusted with calling the offensive plays - from his position at right tackle.

He graduated second in his class, a smart player on a smart team. Four of its members (Olivar, Alex Bell, Art Raimo and John McKenna) would go on to coach at the major college level. And playing right next to Olivar at right guard was a guy named Dave DiFilippo, who years later would achieve a certain measure of fame as the head coach of a legendary minor league team known as the Pottstown Firebirds, and the focal figure in an NFL Films production entitled "Pro Football, Pottstown, PA."

In his senior year, Villanova ended the season by travelling to Los Angeles to play Loyola in the Coliseum. While there, he and some teammates took a bus ride from their downtown hotel out to Santa Monica. The bus stopped on the Palisades, from where they could see the Pacific, with Catalina Island in the distance. He was blown away by what he saw. Then and there, in the words of his son, Harry, "he fell in love with California."

Following graduation from Villanova, now married and with his wife, Stella, expecting twins, he got a job teaching and coaching at Radnor High School, not far from the Villanova campus. After a year at Radnor, he left to coach at Paulsboro, New Jersey, and after two years at Paulsboro, he moved to Philadelphia's Roman Catholic High.

At the same time, exempt from the draft with a wife and two young children, he worked in a Philadelphia shipyard.

And then, a year later, Villanova called. He was 28.

He was the first of three members of his Villanova squad to later coach the Wildcats (Raimo and Bell were the two others). When he took over, it was 1943, war time, and not a good time to be coaching a college team that struggled to find able-bodied players wherever and whenever it could, and had to play the likes of Army's great Blanchard-and-Davis teams. He took his lumps at first, absorbing an 83-0 defeat at the hands of mighty Army, but he built well and managed to compile a 33-20 record in his five seasons at Villanova. Two of his teams went to bowl games: in 1947, Villanova lost to Kentucky - coached by Bear Bryant - in the Great Lakes Bowl, 24-14; and in 1948 his Wildcats finished 8-2-1, including victories over Texas A & M, Miami and North Carolina State, and a 13-13 tie with Coach Bryant and Kentucky. They capped the season with a 27-7 win over Nevada in the Harbor Bowl in San Diego.

It was on the way back from San Diego, during a change of trains in Los Angeles, that he learned that Loyola, the small Catholic school whom he'd once played against, was looking for a football coach. He remembered his first view of the Pacific from the Palisades, and how he'd been taken with California, and decided to get off the train to call Loyola and inquire about the job.

As Harry Olivar told me the story, it was January, 1949, and as his dad got off the train in L.A.'s Union Station to make the phone call, it was snowing! "In California?" he asked himself. "Who needs this? We have snow in Pennsylvania." But he made the call anyhow. He got through to a receptionist, who told him there was no one in the athletic department. "It's Sunday," she reminded him.

He was tempted to say, "That's too bad," and get back on the train, but instead he persisted, asking, "Isn't there someone I can speak to about the football position?"

"You could probably talk to Father Connelly," the receptionist said. "The priests live on campus. He's the Athletic Director."

Coach Olivar managed to get hold of Father Connelly and explain who he was and why he was calling, but the priest cut him off short, telling him, "I think we've already filled the job."

Coach Olivar asked, "Who do you have in mind?"

Father Connelly replied, "Joe Sheeketski, of the University of Nevada."

"Would it make any difference," Olivar asked, "If I told you my team just beat his team, 27-7?"

Said Father Connelly, "Maybe we should talk!"

And so while the Villanova team's train pulled out of Union Station without him, Coach Olivar took a taxi to the Loyola campus to meet with Father Connelly.

Their meeting went well - so well that later that day, Jordan Olivar called his wife, back in Pennsylvania, and told her, "Pack your bags. We're moving to California."

In his three years at Loyola, he built a powerhouse, at one point posting a 13-game winning streak. His 1950 Lions' team, quarterbacked by Don Klosterman, finished the season ranked 22nd in the nation, and led all colleges in passing. Ironically, the 1950 Lions defeated Nevada, 34-7, as Klosterman completed eight of the 11 first-half passes he threw, three for touchdowns, and Loyola outgained Nevada 423 yards to 98.

Six members of that team went on to play professional football, the best-known among them Gene Brito, who would become an all-pro defensive end, and quarterback Klosterman, who would achieve even greater renown as a pro football executive.

But small Catholic schools around the country were being hard-hit by the rising costs of playing big-time football and, one by one, they gave up the fight. Loyola joined them, dropping football after the 1951 season, and Jordan Olivar was out of a coaching job.

Reluctant to leave the West Coast, where he and his family loved the life and where he had begun to build a thriving life insurance business in the off-season, he settled for a job as a part-time assistant to Herman Hickman at Yale. But before Olivar had even had a chance to meet the players, Hickman left to take a job in television. It was already August, and understandably, the Yalies were panicking.

Only one man on the Yale staff - Olivar - had had successful head coaching experience, so in desperation they offered him the job. Olivar hesitated, but not because he didn't think he was up to the job - he just didn't want to have to move his family back East. Finally, he took the job, but with the understanding that he could continue to live in California in the off-season.

The decision proved to be a fortunate one for Yale. Olivar proved to be a godsend, turning potential disaster into triumph by coaching the 1952 team to a 7-2 record. When he left Yale 11 years later, in 1962, he had built a record of 61-32-6, and was the winningest coach in the Ivy League. As a Yale coach, only the great Walter Camp, who retired 70 years before, had won more games. Olivar's 1956 team won the first-ever Ivy League title, and his 1960 team finished 9-0, the first undefeated Yale team in 37 years. He was an American Football Coaches Association Coach of the Year. (He first became a member of the AFCA the same year as another young coach named Paul "Bear" Bryant.)

(His 1960 Yale team finished 14th in the AP poll, last Ivy team to finish that high, and just ahead of number 15 Michigan State and number 16 Penn State. We will not see that again in our lifetime.)

His greatest thrill in coaching came in 1955, when Yale upset Don Holleder-led Army 14-12, in front of a 70,000 people in a sold-out Yale Bowl. He had never forgotten the time that a powerful wartime Army team and its Coach, Earl "Red" Blaik, had poured it on his undermanned Villanova squad, 83-0.

He was an extremely loyal man who inspired a reciprocating loyalty in those who worked for him. He kept the same four assistants - Harry Jacunski, Jerry Neri, Jack Prendergast and Art Raimo - through his entire tenure at Yale. Two of them, Neri and Raimo, were former teammates from Villanova, and they remained lifelong friends.

Although his style of football would be considered conservative today, by the standards of that time, when many teams were still running the old-fashioned single wing, he was considered an innovator.

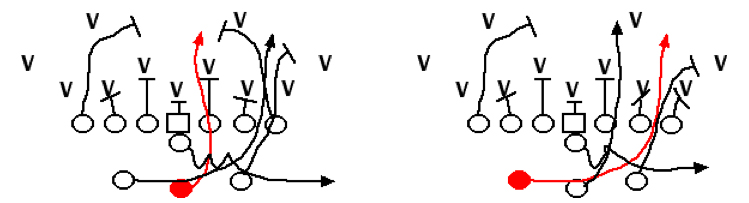

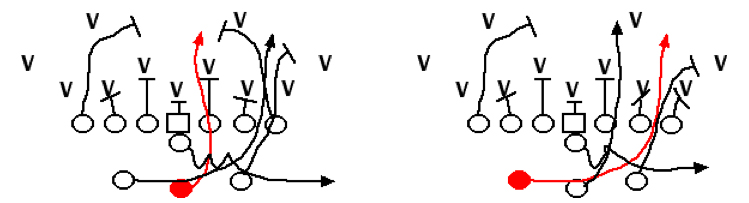

He helped pioneer the Belly-T, or Belly Series (some people at the time called it the Drive Series or the Ride Series, but the name "Belly" won out). One can easily see at first glance, the seeds of the Wishbone T (the name that won out over "Y" formation) that would come along almost a generation later.

The Belly-T is still a highly effective offense. Dewey Sullivan, of Dayton, Oregon, winningest coach in Oregon high school football, ran it well into the 1990s. (Coach Sullivan once paid me the high compliment of saying, "If I didn't run my offense, I'd run yours.") Coach Olivar's book, "Offensive Football - The Belly Series", written in 1958, is still the best I've seen on the subject, and I'd recommend it to anyone interested in the offense - if you can find a copy. Perhaps remembering how he himself had called the plays while playing tackle at Villanova, his system placed a great deal of responsibility on the offensive tackles' ability to recognize defenses and adjust to them by making the appropriate blocking calls.

Now that I know more than I did when I was in college, I recognize Coach Olivar's genius at never attempting to do things that were beyond his players' capabilities. When he had the players to do so, he did more with them. And he never did anything stupid, nor did his teams. That may sound like a "well, duh!" sort of statement at an Ivy League school, but if you believe in multiple intelligences, you will trust me when I say that an Ivy League intellect is not necessarily a guarantee of football intelligence.

He was highly respected by his players. Without being a whipcracker, he had great team discipline.

He was erudite, and he was smart.

I still remember a special teams lesson he taught me, nearly 50 years ago. We had had plenty of good placekickers at Yale, yet none of them ever did our kicking off. Instead, I'd watch, chuckling, while big linemen practiced kicking off. They were lousy at it, and it seemed to me that the more they practiced, the lousier they got. In fact, if I didn't know better, I'd have sworn they were trying to be lousy! I'd just shake my head and go about my business.

After graduation, I took a job that kept me in Connecticut, and one night, my boss invited me to a banquet at which Coach Olivar was the featured speaker. At dinner, I found myself sitting next to him. Now, you have to understand something. We didn't really know each other all that well. He was not a cold individual by any means, but he was a man of enormous dignity and aplomb, and he kept a proper distance from us players. He delegated absolutely, so that all of our interaction with the coaching staff was with our position coaches and not with him. Couple that with the fact that I had been something of a screw-off, an underachiever who undoubtedly was a source of some frustration to the coaches during my years there, and you'll perhaps understand why I didn't know what to expect of our encounter.

But the coach I'd known from a distance couldn't have been more cordial and more enjoyable that evening. I had never done a damn thing for him, but from the moment we sat down that night, he was my coach, and I was one of his former players, and he made me feel like an All-American.

He told me all sorts of stories, as if I was an old friend. (I was reminded of this phenomenon when I heard a former Texas player say of Darrell Royal, "Coach Royal was my coach - and then he became a friend.")

At length, I got up the courage to ask him something that had been on my mind for quite some time: why did we kick off like that?

He threw his head back and laughed. I got the feeling he'd been asked that one a few times before.

He told me that there was a time once when he was just like everyone else - when he had his kickers tee it up and kick it deep. And then one time, after an opponent had run a kickoff back for a touchdown, he applied his intelligence to the problem, and came up with his solution - don't kick it to their return man!

Let the opponents spend all the time they wanted to, he figured. Let them work on their kick return. But they wouldn't get a chance to use it against his team.

Years later, when I first became a coach, and immediately knew all the answers without first having to bother learning them, I had kickers who could boom them deep. Shoot - I had a few guys who would go on to kick in the pros. They could put it in the end zone. So we kicked off deep.

But when I became a high school coach, I began to get tired of spending a lot of time on kick coverage, yet still having to worry every time the ball landed in a return man's arms. Once in a while - not that often, but still too often to suit me - we would have one returned on us. We may have driven the length of the field to score, and yet in one stunning play, a return man had nullified all our efforts. It made no sense to me.

So in my mind I went back to that night when I'd sat next to Coach Olivar and gotten the benefit of his wisdom. And from that point on - some time around 1980, it was - I made the decision never again to kick it deep. Since then, I've seen exactly one kick returned all the way against one of my teams. It was 1996, and the kicker got a little carried away - and kicked it deep! And, less than 20 seconds into the game, we were down, 7-0.

I have, though, done one thing that Coach Olivar didn't do. I have made sure to tell all my players why I do what I do, and I explain to them that I'm telling them so they'll know what to say when Dad or Uncle Charlie ask why we never kick it high and deep,

To show how times have changed since he coached at Yale, Coach Olivar was able to take advantage of the Ivy League's ban on spring practice and its restrictions on recruiting by continuing to coach in the summer and fall and then returning to Los Angeles - and his insurance business - after the season.

Finally, though, he began to feel pressure from alumni and administration to move to New Haven full-time, even to the point of their offering to arrange a transfer of his business to New Haven or Hartford. He declined, however, and following the 1962 season, resigned his position. He was only 47 years old, but he returned to his home in his beloved Southern California to devote full-time to his life insurance business, and never coached again.

Never officially, that is. He was, however, instrumental in helping UCLA, one of the last of the major single-wing teams, convert to the more modern T-formation.

According to his son, Harry, he looked back on his coaching career with no regrets. He derived great satisfaction from it, and considered it a fulfilling career. And then he moved on.

He didn't need football coaching to define him. He had his business and his family, and he was a man of wide interests. He enjoyed playing tennis, he collected Italian stamps and art objects, and he loved opera. He was well-read, given to biographies, history and historical novels, and poetry. And he was a great lover of Shakespeare.

Coach Olivar died on October 17, 1990 at the age of 75. He was survived by Stella, his wife of 54 years, his twin children, Harry and Harriet, and nine grandchildren. The cause of death was mesothelioma, a form of lung cancer attributed to his exposure to asbestos while working years earlier in the shipyards.

At his request, his ashes were scattered at the top of the Palisades, the place where he first saw the Pacific.

Jordan Olivar is a member of the Villanova and Loyola-Marymount Halls of Fame, and was elected to the Helms Athletic Foundation Hall of Fame. (Yale has no Hall of Fame, but if it did, Jordan Olivar would surely be in it.)

In his honor, the Jordan Olivar Award is given annually to a Yale senior other than the captain who, through his devotion to Yale football, has earned the highest respect of his teammates.

The Jordan and Stella Olivar Scholarship is awarded annually by Loyola-Marymount to a financially-deserving student-athlete.

Through the years, in the many inspirational speeches he gave to students and businesspeople alike, Coach Olivar would tell the story of his hiring by Loyola, and ask his audience to consider:

What if he hadn't met that wrestler in the gym? What if he hadn't impressed him with his handball game?

What if he'd never gone on that bus out to Pacific Palisades?

What if he hadn't gotten off the train in Los Angeles? What if, after seeing snow in Southern California, he'd gotten back on?

What if he'd accepted the receptionist's explanation that it was Sunday, and everything was closed?

What if he'd accepted the Athletic Director's explanation that he'd already filled the head coaching position?

What if he hadn't taken the part-time position at Yale, after Loyola gave up football?

He would ask those questions to make two important points -

Often, the direction of a person's life is determined by seemingly small turns of events;

Always, success comes from pressing on.

Jordan Olivar was born Giordano Aurelio Olivari in 1915, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Italian immigrants. His father had jumped ship in New York, and later, Coach Olivar would enjoy telling people that his father was an early illegal alien. His father supported his family waiting on tables, and picked up a little money on the side as a boxer.

Jordan Olivar was born Giordano Aurelio Olivari in 1915, in Brooklyn, New York, the son of Italian immigrants. His father had jumped ship in New York, and later, Coach Olivar would enjoy telling people that his father was an early illegal alien. His father supported his family waiting on tables, and picked up a little money on the side as a boxer.